Walking the Medicine Trail with Richard Wagamese and A.B. Guthrie

Sometimes, deep inside a good novel, you feel the throbbing lifeblood of its author—an agony that shines at the edges with a certain ecstasy, like gazing at the ceiling in the Sistine Chapel and feeling the anguish of Michelangelo in every brushstroke.

The hand of the artist has become one with the hand of God, and our own lives are touched by both.

I come late to the books of Ojibwa

writer Richard Wagamese, but his novel Medicine Walk touches the reader with this same authenticity—the bittersweet pain

and joy of the human experience—as lived by the author and expressed through

his characters.

In the essay “Returning to Harmony”

(appearing in the collection Speaking

My Truth), Richard Wagamese writes of his own childhood:

“When I was born, my family still

lived the seasonal nomadic life of traditional Ojibwa people. In the great

rolling territories surrounding the Winnipeg River in Northwestern Ontario,

they fished, hunted, and trapped. Their years were marked by the peregrinations

of a people guided by the motions and turns of the land. I came into the world and

lived in a canvas army tent hung from a spruce bough frame as my first home. The

first sounds I heard were the calls of loon, the snap and crackle of a fire,

and the low, rolling undulation of Ojibwa talk… But there was a spectre in our

midst.”

Like Wagamese (who would be

separated from his Ojibwa family for twenty years), the main character in Medicine Walk, sixteen-year-old Franklin

Starlight, grew like a sapling up out of the land, “hearing symphonies in wind

across a ridge and arias in the screech of hawks and eagles, the huff of

grizzlies and the pierce of a wolf call against the unblinking eye of the moon.

He was Indian.”

But there was a specter in his midst,

too. Raw-boned and angular, Franklin leaves the old man and mountain that

reared him to retrieve his liquored-up father from a one room hovel where he is

living out the last days of a tortured life. The father wants to die in the

warrior way of his people. Duty bound, Franklin agrees to lead his father back into

the mountains. Tethered to a saddle on the back of a faithful old mare so that

he won’t spill onto the ground, the father is led by his son on a journey that

pulls them both through untold stories and unwanted memories.

Medicine

Walk is epic in scope, in part because of the timeless, generational

themes, but also because it shows us the broad, deep scope of the human heart.

The story has a familiarity about it because we find bits of ourselves inside

each character. We know the bittersweet

taste of our own agony and ecstasy, and so we can intuit what it is to be young

Franklin, or dying Eldon, or to be like the old man, valuing love and loyalty

above blame or sorrow.

When confronted with the herculean

task of painting the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo escaped to the mountains and found

inspiration in nature. The mountains are also where young Franklin finds solace

and purpose. It is in nature’s steep ravines that he hides the empty chasms of

his heart.

In Wagamese’s essay “Returning to

Harmony," we begin to understand how young Franklin came to inhabit the fictional

pages of Medicine Walk. We glimpse

the steep ravine of the author’s own life when Wagamese writes about his family:

“Each of them had experienced an

institution that tried to scrape the Indian off of their insides, and they came

back to the bush and river raw, sore, and aching. The pain they bore was

invisible and unspoken. It seeped into their spirit, oozing its poison and

blinding them from the incredible healing properties within their Indian ways.”

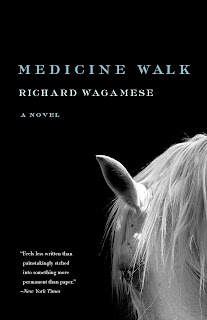

If the job of a novelist is to invite

the reader into a world at once new and unexplored, yet so familiar that we

wear it like an old flannel jacket, then Wagamese was the kind of novelist you

want guiding you through this uncharted terrain. The New York Times, in their review of Medicine Walk, said that the novel felt more like it was etched

rather than written.

Like writer A.B. Guthrie, Wagamese has left

a permanent mark on the literary landscape of America. Young Boone Caudill (from

Guthrie’s novel The Big Sky) shares Frank Starlight’s prowess and intensity. On the brink of manhood, Boone

leaves the backwoods of Kentucky and the hard knocks of a drunken father with

nothing but an old, sure shot rifle and a roasted hen, still warm, wrapped

inside a greasy rag. Boone leaves for the wilderness knowing all he needs to

know about his family, but nothing about the West.

Like writer A.B. Guthrie, Wagamese has left

a permanent mark on the literary landscape of America. Young Boone Caudill (from

Guthrie’s novel The Big Sky) shares Frank Starlight’s prowess and intensity. On the brink of manhood, Boone

leaves the backwoods of Kentucky and the hard knocks of a drunken father with

nothing but an old, sure shot rifle and a roasted hen, still warm, wrapped

inside a greasy rag. Boone leaves for the wilderness knowing all he needs to

know about his family, but nothing about the West.

Franklin knows all he needs

to know about the wilderness, but nothing about his family. Both boys enter

uncharted lands. “Taking life was a solemn thing,”

young Franklin thinks to himself as he considers hunting, and the mystery of

life. Tracking, for him, is to slip out of the bounds of what he knows of

earth, and "outward into something larger, more complex and simple all at once.

He had no word for that."

But a cry born of a loss? That he slowly came to

understand was a part of him forever.

A.B. Guthrie, who won the Pulitzer

Prize for Fiction in 1950, died in 1991. Richard Wagamese passed away on March

10, 2017, after writing more than a dozen books. When the hand of the

artist truly does become one with the hand of God, we feel our own lives touched by

both, the art we love etched in the soft stone of our heart.

Note: Read Wagamese's entire essay "Seeking Harmony" as published in Speaking My Truth.

Note: Go to Richard Wagamese's author website.

Note: Buy Medicine Walk from Milkweed Editions.

Comments